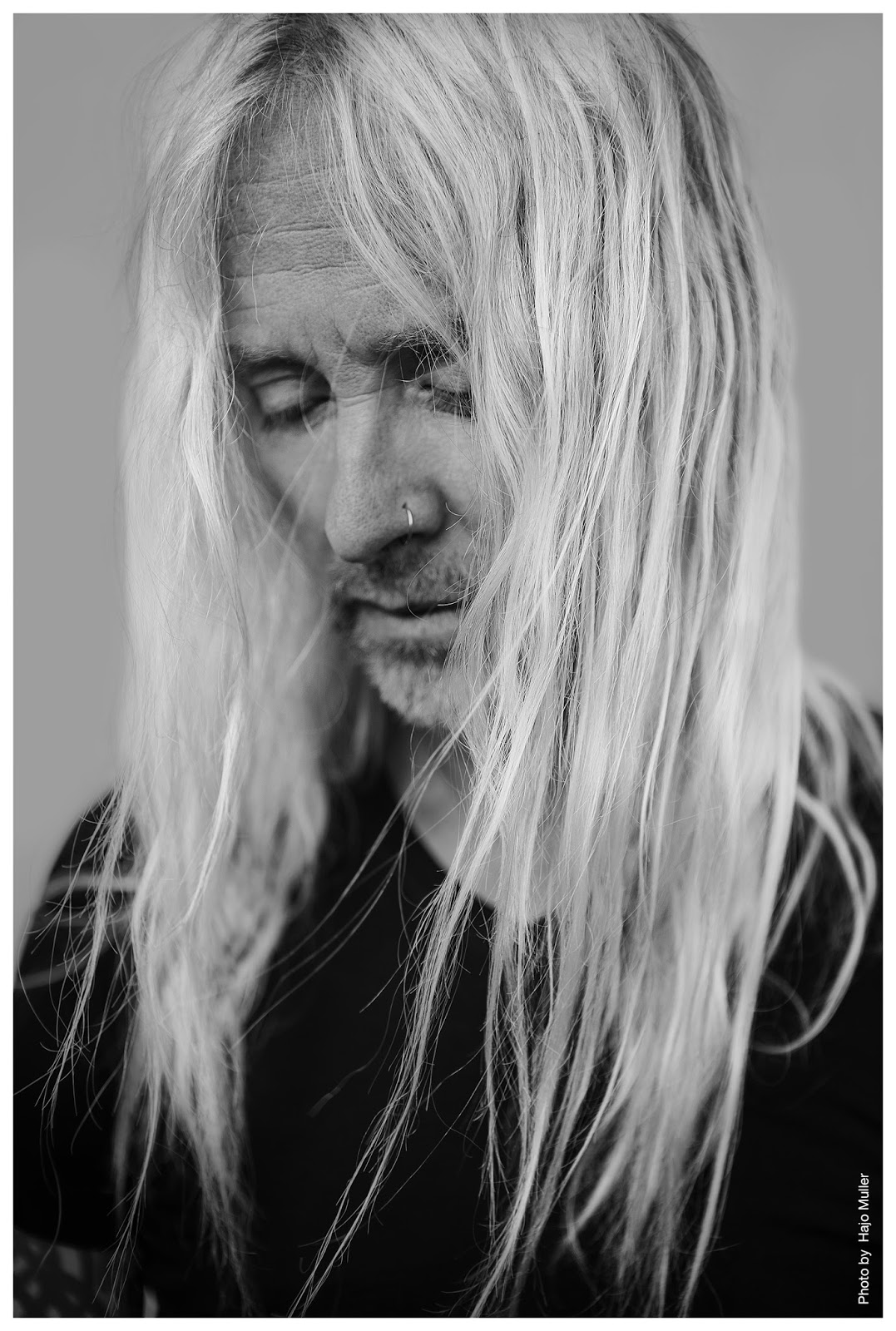

Z okazji nadchodzącej wielkimi krokami premiery płyty „tardigrades will inherit the earth” miałem przyjemność porozmawiać z głównodowodzącym tego projektu, czyli wszędobylskim Nickiem Beggsem. Zdradził mi on dalsze plany grupy, opowiedział o tym, co można znaleźć w okolicach jego odtwarzacza winyli, ale też podzielił się swoim krytycznym spojrzeniem na to, w jakim kierunku podąża świat. Premiera nowego albumu jego zespołu the Mute Gods będzie miała miejsce 24 lutego.

Dawid Zielonka: W trakcie słuchania nowego albumu the Mute Gods staje się jasnym, że to już wasze własne brzmienie i to, co mogliśmy usłyszeć na debiucie nie było wypadkiem. Czy od początku wiedziałeś, jak będzie brzmieć ten zespół, czy stało się to dopiero jasne, kiedy zaczęliście wspólnie tworzyć?

Nick Beggs: Myślę, że złożyło się na to wiele elementów, które chciałem włączyć w brzmienie tej płyty i projektu w ogóle… masz rację, musiało to charakteryzować się brzmieniem, które odzwierciedlałoby the Mute Gods. Dokonanie tego za pierwszą próbą jest dość trudne, dlatego też na pierwszej płycie więcej eksperymentowałem z różnymi stylami pisania. Wpłynęło na to też posiadanie 3, 4, a nawet 5 partnerów pomagających mi przy tworzeniu materiału. Wydaję mi się, że jak już wypuściłem pierwszy album, nauczyłem się bycia obiektywnym w tej materii. Miałem lepsze pojęcie na temat tego, co chciałem zawrzeć na drugim krążku, z tego też względu czułem większą pewność siebie, aby przejąć kontrolę nad procesem twórczym. To właśnie tym razem zrobiłem. Napisałem wszystko sam, dzięki czemu miałem poczucie większej kontroli nad brzmieniem. Myślę, że będę dalej dążyć w tym kierunku, a na trzeciej płycie będę mógł już tworzyć zupełnie bez strachu.

DZ: Wygląda też na to, że zdecydowałeś się ograniczyć skład do waszej trójki. Co do tego doprowadziło?

NB: Tak, trzech podstawowych muzyków – tzw. power trio. Do tego dwóch gości na płycie na wokalach wspierających – moja córka i córka Rogera Kinga. Ich wokalne wsparcie wprowadza dużo kolorytu. Chciałem też zaprosić do jednej piosenki mojego siostrzeńca, który rapuje i pisze poezję, ale jakoś nie za bardzo to działało, ale obecność córki na albumie była czymś wspaniałym.

DZ: Opowieści przedstawione w nowych utworach są dość posępne, niektóre nawet niepokojące. Czy mógłbyś nam przybliżyć, co chciałeś przez nie przekazać?

NB: Ten album to uznanie… uznanie naszej kruchości, głupoty i niechybnego upadku. To właśnie jego sedno. Wykluczając ostatni utwór, który jest piosenką miłosną, która rzuca prawdopodobnie jedyne promyki słońca na ten album. Reszta jest o kruchości, głupocie i śmierci ludzkości.

DZ: Ciekawi mnie, jak to jest, że piszesz o tych wszystkich przerażających rzeczach, a melodie mają pozytywny wydźwięk. Czy to było zamierzone?

DZ: Pracowałeś w swojej karierze z wieloma utalentowanymi muzykami. Czy jest wciąż ktoś z kim nigdy nie współpracowałeś, a marzysz o tym?

NB: Oczywiście, że tak. Jest tylu świetnych muzyków, z którymi chciałbym współpracować. Jest z kogo wybierać. Sęk w tym, że nadszedł czas, abym został artystą z prawdziwego zdarzenia. Jestem zadowolony z ludzi, z którymi pracuję i jeśli ktoś nowy chciałby ze mną pracować, myślę, że bym odmówił. Mając 55 lat, jestem w momencie swojego życia, kiedy zmieniam się w sposób, w jaki nigdy nie sądziłem, że jeszcze będę, więc moje priorytety się mocno zmieniły i zamiast uganiania się za pracą z innymi utalentowanymi muzykami i chęci pracy z nimi, próbuję ugruntować swoją pozycję samodzielnego artysty.

DZ: Skoro jesteśmy przy temacie artystów, z którymi współpracowałeś, powiedz mi, czy jesteś zaangażowany w prace nad nowym albumem Stevena Wilsona?

NB: Tak, nowy album jest już nagrany i Steven jest w trakcie miksowania go.

DZ: Czy masz zazwyczaj dużo do powiedzenia artystycznie na jego krążkach, czy rządzi Steven i jego pomysły?

NB: Steven ma podobne podejście do swoich albumów jak ja do płyt the Mute Gods. Piszę muzykę i zapraszam wszystkich do zrobienia tego, co robią najlepiej. W dawaniu ludziom wolności w pewnych sferach, w których potrzeba upiększyć materiał, jest element kreatywności. Steven ma właśnie takie same podejście. Ma wybitne i nieugięte opinie na temat tego, gdzie pewne pomysły powinny zmierzać, ale jest w stanie dać ci tę mglistą przestrzeń na wyrażenie siebie. Dobry pomysł jest dobrym pomysłem. Jeśli coś działa, jest na to otwarty.

DZ: Nick Beggs wraca do domu po dniu ciężkiej pracy. Jaką muzykę włącza, żeby się zrelaksować?

NB: Niczego bym nie włączył. Jeśli już słucham muzyki, jest to zazwyczaj muzyka klasyczna. W sumie to spojrzę na mój odtwarzacz winyli i powiem ci, czego słuchałem w ostatnich miesiącach. Dobra, co my tu mamy? Prince & the Revolution “Parade”, Black Sabbath “Sabotage”, Jethro Tull “Songs from the Wood”, Prince “Around the World in a Day” i Michael Franks “One Bad Habit”, mam też Pat Metheny Group “Offramp”, a i jeszcze John Foxx “Metamatic”.

NB:Tak, jest tego więcej.Mam też jeszcze starsze rzeczy. Roxy Music “Flesh and Blood” i The Slits “Cut”. Tak, całkiem różnorodne rzeczy.To nie te klasyczne albumy, których słucham. Mam jeszcze osobną sekcję z muzyką klasyczną.To tylko winyle, a słucham też rzeczy w cyfrowym formacie na laptopie, ale często nie mam ochoty słuchać muzyki, bo jestem zbyt zmęczony i wolę posłuchać audycji z rozmowami, czegoś na miarę Radio 4, lub obejrzeć serial telewizyjny.

DZ: Wyczytałem, że nie chciałeś podpisać kontraktu ze Skunk Anansie, kiedy pracowałeś dla Phonogramu. Muszę powiedzieć, że kocham ten zespół. Jak brzmieli w tamtych czasach?

NB: Nie nazywali się wtedy Skunk Anansie. To czasy przed tym. Myślę, że byli w trakcie rozwoju, to był dopiero zalążek ich stylu, coś w nich było, ale nie do końca to dostrzegałem. Widziałem Cassa (basista Skunk Anansie – przyp. red.) parę dni temu. Jest moim dobrym przyjacielem. Znamy się od czasów, kiedy grał w zespole Terrence’a Trenta D’Arby’ego. Grupa wciąż gra koncerty i miała świetną karierę… wciąż ma. Cieszy mnie to bardzo.Myślę, że ludzie zajmujący się A&R (dział arstystyczny firmy fonograficznej – przyp. red.) wcale nie wiedzą, czym jest hitowy album, nikt tego nie wie, mimo że nam się zdaje, że wiemy. Pakujesz dużo pieniędzy w znalezienie kolejnego Rage Against the Machine czy czegokolwiek tam szukasz. Wciskasz kit i uprawiasz polityczne gierki. Było mnóstwo rzeczy, które przeszły przez moje biurko, których potencjału nie dostrzegłem i były też zespoły, z którymi miałem hity. Wszystko sprowadza się do liczb. Frank Zappa miał ciekawą opinię na ten temat.Powiedział, że w dawnych czasach nagrywania płyt i branży A&R zarządcy dywagowali: “Nie rozumiem tego. Młodzież to lubi? Nie wiem, czy to jest dobre. Myślisz, że to dobre? Wypuśćmy to.Spróbujmy szczęścia”. Czasem był to sukces, a czasem nie. Potem pojawiły się te młodziaki, a byłem jednym z nich, które zaczęły gadać, że wiedzą, co jest dobre dla ludzi do słuchania. Lepiej nam było, zanim się pojawili, bo oni też nie wiedzieli, co jest dobre. Wszystko stało się bardziej korporacyjne, zmieniła się polityka, było więcej zagarniania pieniędzy i były te młodziaki niewiedzące, jak wypuścić przełomowy album. W pewnym sensie się z tym zgadzam i muszę przyznać się z ręką na sercu, że byłem jednym z tych ludzi. W ten sposób działa przemysł muzyczny.

DZ: Jesteś bardzo wszechstronny, jeśli chodzi o granie różnych gatunków muzycznych. Synthpop, progresja, folk, muzyka celtycka… nie istnieją dla ciebie granice. Gdybyś był absolutnie zmuszony grać jeden gatunek muzyczny przez resztę życia, jaki by to był?

NB: [Westchnienie i długa cisza] Dobra, jeśli miałbym grać tylko jeden gatunek muzyczny do końca życia i mógłbym się z tego utrzymać, byłby to jazz, ponieważ jest to coś, czego nie umiem grać, tym samym musiałbym się go nauczyć i studiować go, bo jest on podobny do muzyki klasycznej. Jest to zupełnie inny język.Jest to gatunek, który stoi na uboczu i musi być zrozumiany. Jest bardzo wymagający i skrywa w sobie wiele aspektów. Zawsze chciałem móc grać jazz i beatboksować, i tworzyć w tych stylach, ale z powodu braku pieniędzy z nich, nigdy się ich nie nauczyłem. Muzycy jazzowi w większości mają trudności z utrzymaniem się z grania muzyki i nawet Miles Davies kiedyś powiedział, że jazz nie niósł ze sobą dużej ilości pieniędzy nawet, kiedy był już sławny. Więc gdybym mógł zarobić na życie jako muzyk jazzowy, byłby to gatunek, który bym wybrał, ponieważ jest jednym z najbardziej ekspresyjnych, improwizacyjnych i w pewnych aspektach najbardziej wymagających gatunków. Musisz mieć wiedzę, wielkie predyspozycje i umieć grać bez prób. Jeśli więc miałbym wybrać jeden gatunek muzyczny i mógłby on zapewnić mi stały przychód, byłby to jazz, ale to niemożliwe, bo nie da się wyżyć z jazzu.

DZ: Może byłoby to po prostu hobby. Coś, co byś robił dla przyjemności.

NB: Cóż, nie robiłbym tego wtedy, bo muszę zarobić na życie. Muszę utrzymać dom i zapewnić pieniądze mojej rodzinie, a to by mi na to nie pozwoliło. Nie grałbym chyba muzyki w ramach hobby. Dla mnie to musi być wszystko albo nic. Musiałbym się temu w pełni oddać lub po prostu to porzucić.

DZ: Patrząc na listę zespołów, w których grałeś, i projektów pobocznych, w które byłeś zaangażowany, muszę zapytać, jak znajdujesz na to wszystko czas?

NB: Nie jest to takie trudne. To w sumie dwie proste rzeczy: myślenie i zarządzanie czasem. Ot cały sekret. Jeśli rozważasz pewne rzeczy i rozplanowujesz je umiejętnie czasowo, możesz dokonać wszystkiego. Mógłbym robić jeszcze więcej, ale nie chcę, bo lubię mieć wystarczająco czasy, żeby się znudzić… no, ale nie jest to żadną tajemnicą. Gdybyś mógł naprawdę przysiąść i przemyśleć wszystko logistycznie, wszystko, czego potrzebujesz, żeby tego dokonać, umiejętne zarządzanie czasem wcale nie byłoby takie trudne.

DZ: Muszę się przyznać, że nigdy nie interesował mnie Chapman Stick. Jesteś kimś, kto uatrakcyjnił dla mnie ten instrument. Kiedy usłyszałem “The Darkness in Men’s Heart”, byłem pod wielkim wrażeniem. Kto sprawił, że ten instrument stał się atrakcyjny dla ciebie?

NB: Wynalazcą Chapman Stick jest pan, który mieszka w Kalifornii. Nazywa się Emmett Chapman i tworzy ten instrument od lat 60. Jest moim dobrym przyjacielem i inspiracją, więc to on jest osobą odpowiedzialną za moje zainteresowanie tym instrumentem.

DZ: Na obydwu okładkach swoich albumów pojawia się dziwna postać w garniturze z ekranem bądź lustrem zamiast głowy. Co ona dla ciebie symbolizuje i czy ma jakieś imię?

DZ: Muszę przyznać, że jest to jeden z najgłębiej przemyślanych opisów postaci ukazującej się na okładce albumu, jaki kiedykolwiek słyszałem.

NB: Myślę, że to bardzo wyrazista i frapująca ikona. Mówi ona sama za siebie i będę jej konsekwentnie używać jako przekazu dla całego świata, ponieważ musi on się przebudzić, sama religia musi się przebudzić. Musimy na siebie spojrzeć i dojrzeć siebie. Nie ma boga. To my jesteśmy odpowiedzialni za to, co dzieje się na świecie. To my sprawujemy pieczę nad nim i to my ją utracimy z własnego powodu, z powodu naszej głupoty.

DZ: Co dalej z the Mute Gods? Czy pozostaną sprzeczni ze swoją nazwą?

NB: Słucham? Czy pozostaną sprzeczni ze swoją nazwą? [śmiech] Pracuję już nad trzecim albumem i będzie trzeci album, jeśli uda mi się go wypuścić w ciągu roku lub w okolicach roku. Najlepiej jakoś o tej samej porze roku co ten. Ludzie pytają, czy zagramy na żywo i naprawdę nie wiem, ponieważ to zależy od tego, czy znajdzie się na nas popyt. Jeśli ludzie będą chcieli przyjść nas zobaczyć, kupią bilety i płytę, to zbiorę zespół i zagramy parę koncertów, ale za wcześnie, by wyrokować.

DZ:Dziękuję za wywiad i pozdrowienia z Polski.

NB:Dzięki, Dave.

———- ENGLISH VERSION ———-

Dawid Zielonka: After listening to the Mute Gods’ new album it becomes clear that this is your sound and what we can hear on your debut was no accident. Did you know from the start what would this band sound like or it was something that became clear when you started creating together?

Nick Beggs:I think there was a lot of elements that I wanted to amalgamate into the record and for the overall sound of the project… and you’re right, it had to have a signature that sounds like the Mute Gods. And to hit that straight off is quite difficult, so I think on the first record I was experimenting a lot more with different songwriting themes, cause I had 3 or 4 or 5 different partners helping me with the material. I think once I released that first record, I learnt how to be objective about it. I was more determined about which parts to take to the second one, therefore felt more capable of taking charge of writing the material on my own. And that’s what I did this time. I wrote everything, and therefore felt that I had more control over the sound. I think that will only develop now, because on the third record I can go forward unabashed.

DZ: It also seems you settled on just the three of you on this record. What’s the reasoning behind it?

NB:Yeah, the three core musicians – the power trio. Two additional guests on the recording on backing vocals on two songs – my daughter and Roger King’s daughter. They just add some backing vocals which adds quite a lot of colour actually. I tried to have my nephew on one song, cause he raps and he writes poetry, but it kind of didn’t really work, but to have the daughter on it, it was great.

DZ: The stories told in the new songs are quite grim, some even disturbing. Could you tell me a bit more about what you wanted to say through them?

NB:This album is an acknowledgement. It’s an acknowledgement of our fragility, our stupidity and our impending demise. And that’s it really. Apart from the last song, which is a love song that has probably the only ray of light on the record. The rest of the record is about the fragility, stupidity and the death of mankind.

DZ: The interesting thing is that you write about those horrifying themes and yet all the melodies seem positive. Was it intended?

NB:Well, I think quite a lot of them, for instance „Tardigrades…”, are buried in a major key, but it develops in a minor kind of way, so you have this rather unsettling sense about it. It’s almost like the smiling Axeman. I think the record has a quality of a smiling Axeman about it or the Grim Reaper, he’s wearing a smile looking at you. And I think that there’s a sweetness to my voice when I sing in a certain way. I wanted to kind of make it melodic, there’s also an anger on the certain tracks that I’ve gone almost on a chanting, ranting vocal spur. I experimented with more dark vocal tones than I’ve ever done before and I found some new styles on certain songs which I’m going to develop further on the further albums. So there’s a whole array of vocal styles in there, giving information and telling stories of our freedom as I see them, getting the ideas across. And I think that’s one of the unsettling things about the record, because it doesn’t really give you a chance to really know what’s going on. I think after listening to the album you can actually ask a question is it really serious, do you really believe this stuff?

DZ: You’ve worked with a lot of talented musicians in your career. Is there still someone you haven’t worked with yet that you dream of working with?

NB:Yes, of course. There’s so many great musicians out there that I’d love to work with. You could take your pick. The thing is, it’s time for me now to become an artist in my own rights. I’m very happy with the people that I’m working with and if people wanted me to work with them, I don’t think I’d do it. I’m kind of, at the time, at 55 I’m reinventing myself in a way that I never thought I would, so my focus has changed quite a lot from chasing or longing to work with other great musicians to trying to establish myself as an artist in my own rights.

DZ: Speaking of the artist you’ve collaborated with… Tell me, are you currently involved in the creation of Steven Wilson’s next album?

NB:Yes, the new album has been recorded and he’s in the process of mixing at the minute.

DZ: Do you usually have much to say creatively on his albums or is it just Steven and his ideas?

NB:Steven takes the same sort of approach to his albums as I do with the Mute Gods really. I kind of write the material and get everyone to play their thing. There’s an element of creativity, giving people freedom in a few areas when it needs to be embellished. Steven takes the same approach really, you know. He has great, strong ideas about where certain things should go, but he will afford you that nebulous area of self-expression. A good idea is a good idea. If something’s working, he’s open to that.

DZ: Nick Beggs comes back home after a day of hard work, what does he put on to relax?

NB:I wouldn’t put any music on. If I listen to music I usually listen to classical music. I can tell you, I will look at my vinyl and go to the last records I played on the turntable in the past months. Ok, what have we got here? Prince and the Revolution “Parade”, Black Sabbath “Sabotage”, Jethro Tull “Songs from the Wood”, Prince “Around the World in a Day” and Michael Franks “One Bad Habit”, and then I’ve got Pat Metheny Group “ Offramp”, and then John Foxx “Metamatic”.

DZ: Pretty varied collection.

NB:Yeah, it goes on. It goes back further than this. Roxy Music “Flesh and Blood” and The Slits “Cut”. Yeah, that’s quite varied. That’s not the classical stuff I’ve been listening to, but I have another classical section which I’ve been listening to. That’s just the vinyl, cause I listen to stuff on digital format on my laptop, but very often I don’t want to listen to music because of being tired and I just want to listen to either talk radio, something like Radio 4 or watch some streaming TV shows.

DZ: I read you wouldn’t sign Skunk Anansie when you worked for Phonogram. I must say I love the band. What did they sound like back then?

NB:Well, they weren’t called Skunk Anansie then. It is before. I think they were developing, they were embryonic, there was something there, but I couldn’t see it. I saw Cass (Skunk Anansie’s bassist – editor’s note) the other day actually. Cass is a good friend of mine. I knew him since he was in Terrence Trent D’Arby’s band. They’re still touring, they had a great career and they still do. And I’m really pleased with them. I think A&R men don’t really know what a hit record is, none of us do, you think you do. You put a lot of money to find the next Rage Against the Machine or whatever it is, you know. You bullshit and play the political game. There was a whole lot of bunch of stuff that came through my desk that I’ve missed and then there was stuff that had hits with too. It’s a numbers game. Frank Zappa had a very good take on this. He said that in the old days of doing records and A&R-ing a bunch of executives would go: “I don’t understand this stuff. The kids are really into it? I don’t know if it’s good. Do you think it’s good? Put it out. Let’s take a chance on them”. Sometimes it would be successful, sometimes it wasn’t. But then these young kids came along, and I was one of those too, and they started saying they knew what was good for people to listen to. We were all better off before those kids came along that thought they knew what was good for us, because they didn’t know either. It became more corporatized then. It was more political, there’d be more money grabbing, there’d be those young kids not knowing how to release those hit records. I kind of agree with it, and I have to hold my hand up and say „I was one of those guys”. That’s the way the music industry works.

DZ: You’re quite versatile when it comes to playing different types of music. Synthpop, progressive, folk, celtic… there’s really no boundaries for you. If you were absolutely forced to limit yourself to playing only one genre for the rest of your life, what would it be?

NB: [Sigh followed by a long pause] Okay, If I had to play one genre for the rest of my life and I was going to make a living of it, it would be jazz, because it’s something I can’t play, and therefore I would have to learn it, and I would have to study it, because it’s like classical music. It’s another language of its own. It’s a genre that stands alone and has to be understood. It’s very demanding and it comes with many aspects to it. I’ve always wanted to be able to play jazz and beatbox, and do those styles of music, but because there’s no money in it, I haven’t. Jazz musician by and large find it very hard to make a living and Miles Davis even said jazz wasn’t paying much even when he was famous. So, you know, If I could make a living as a jazz musician, it would be the one I’d choose because it’s one of the most expressive, the most improvisational, on some level the most demanding styles, because you need to have all the information at your disposal, you have to have a great facility, be ready to go without rehearsals. So if I had to pick one and it would afford me a steady income, it would be jazz, but it wouldn’t, because you can’t make a living out of jazz.

DZ: I guess it would be just a hobby then. Something you’d do for pleasure.

NB:Well, I wouldn’t do it then, because I have to make a living. I have to bring money to my home, to my family, so that would exclude that because I wouldn’t be able to do that. I don’t think I would play music as a hobby. It has to be all or nothing for me. I have to do the whole thing or none at all.

DZ: Looking at the whole list of groups you’ve played in and all the side projects you’ve done, one has to ask: how do you find the time for all of it?

NB:It’s not that difficult. It’s actually two simple things: it’s thinking and time management. That’s all it is. If you think about things and get them organized and manage it time appropriately, you can do anything. I could do a lot more, but I choose not to, because I like to have some time to get bored… but it’s not that much of a secret. If you could really sit down and think in terms of logistics, what you need to do to make something happen. It’s not that difficult to manage your time efficiently.

DZ: I must admit I never really cared about the Chapman Stick. You’re the person that made this instrument attractive to me. When I heard “The Darkness in Men’s Heart” I was massively impressed. Who was the person that made this instrument attractive to you?

NB:The inventor of the Chapman Stick is a gentleman who lives in California and he’s name is Emmett Chapman and he’s been making that instrument since the 60s and he’s a good friend of mine, a great inspiration, so he’s the gentleman who’s responsible for that.

DZ: On both covers of your albums you have this weird character with some sort of screen or a mirror instead of a head, always wearing a suit. What does he represent for you and does he have a name?

NB:Yes, he’s called the Mirror Man and he’s a metaphor for religion. He’s a metaphoric religious image. He represents the face of the Gods that we have created. He has no methods of communicating with us, because he’s a construct. We created him. I created him. Therefore, if you look at one of his faces, he has five if you look down on him, you will see yourself and you will relate to that image between you and the reflection and you will draw your own conclusions based on your ideas of what he is and what you are. It’s a direct correlation between our creation of Gods and religion. That’s where the Mute Gods come from, because, in my opinion, we are living in the time where we have religious zealots and hate preachers and radicalized individuals speaking out in the name of God, on his behalf, and yet God stays strangely mute, he never says anything in response and that is the essence, the paradigm of the Mute Gods.

DZ: I must say it’s the most well though characterization of any character appearing on an album cover I’ve heard.

NB:I think it’s a very strong and compelling image. I think it speaks volumes and I’m gonna use it consistently as a message to carry across to the world, because it needs to wake up, and just religion alone needs to wake up. We need to look at ourselves and see us. There is no God. We are responsible for what we do in this world. We have sole stewardship of this world and we’re gonna lose it, because of us, because of our stupidity.

DZ: What’s next for the Mute Gods? Will the stay contradictory to their name?

NB:I’m sorry? Will they stay contradictory to their name [laughs]? I’m working on the third record already and there will be a third record if I can get it released within a year or just around a year. This time next year I’d like to have the third record released. People ask me if we’re going to play live and I really don’t know, because it depends on how much of a market there is for us. If the audience wants to come see us and they buy tickets, they buy the record, then I would put the band together live and play some shows, but it’s too early to know.

DZ: Thank you for the interview and greetings from Poland.

NB:Thank you, Dave.